[!INFO]

This article was previously available to members only. As of January 3, 2026, it has been made publicly accessible.

[!NOTE]

This post and the linked tool are provided strictly for educational and personal-use purposes. The tool does not bypass DRM, encryption, or access restrictions and works only with publicly accessible content—content you can already stream in your browser. What you do with it is your responsibility. Respect copyright law and platform terms.

Introduction

I wasn’t trying to start a debate about copyright, media policy, or digital rights. I wasn’t trying to make a statement or prove a point. I was packing for a train ride, knew I wouldn’t have reliable internet, and wanted to watch Tatort. ARD Mediathek had the episode available, which should have been the end of the story.

It wasn’t.

While the episode was perfectly streamable, downloading it in any meaningful or user-controlled sense was not an option. What should have been a trivial, everyday use case turned into unnecessary friction. That gap between what is technically possible and what users are permitted to do is what this post is about.

Why This Is a Problem

ARD technically offers an “offline mode” through its mobile app. On paper, that sounds reasonable. In practice, it is time-limited, device-bound, restricted to a single application, and intentionally opaque.

You don’t receive a video file you can archive, move, or play freely. You receive temporary permission under strict conditions, bound to a specific app, device, and time window.

At the same time, there is an inconvenient technical truth that streaming platforms rarely spell out clearly: streaming is, technically, downloading.

Your browser must fetch video data onto your machine in order to play it. The difference is not whether data is downloaded, but how it is delivered and handled. Streaming data arrives in small chunks, is abstracted behind a polished interface, buffered temporarily, and usually discarded automatically after playback.

ARD Mediathek, like most modern platforms, relies on HTTP Live Streaming (HLS). Instead of a single video file, the site serves a playlist file (.m3u8) that references hundreds of small media segments. Your player assembles these segments dynamically based on bandwidth and playback conditions.

This approach is efficient and scalable for providers—but fragile and limiting for users, especially when offline access matters.

What I Built

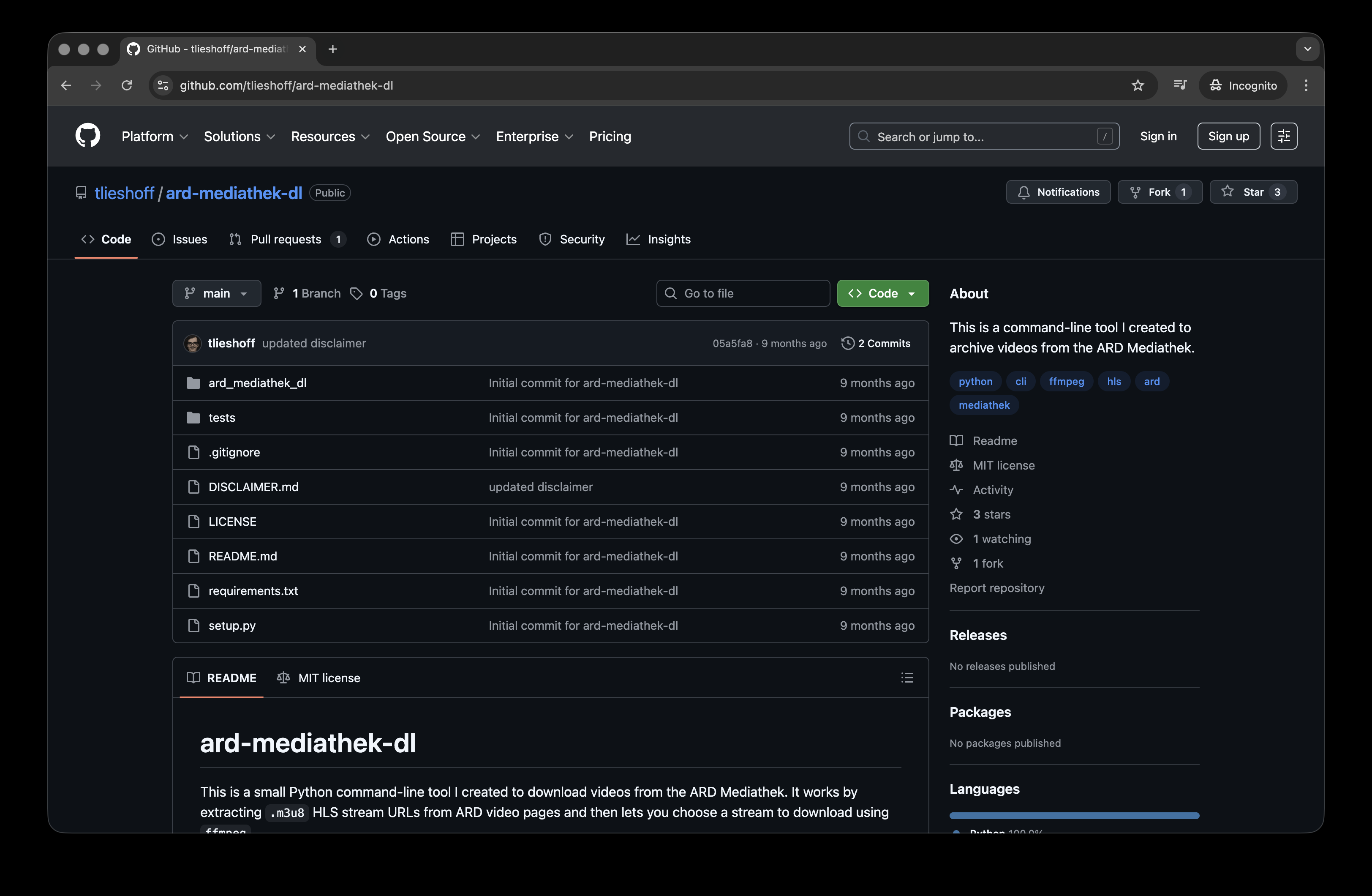

To deal with this, I wrote a small command-line tool called ard-mediathek-dl. Its scope is intentionally narrow: it extracts the actual HLS stream URL from an ARD Mediathek page.

That’s it.

The tool does not remove DRM, decrypt streams, or circumvent technical protections. Once the HLS playlist URL is available, it can be passed directly to ffmpeg, which already supports downloading and merging HLS streams into a single playable file.

If a browser is allowed to play a stream, ffmpeg is technically capable of saving it. There is no clever trick involved here—just standard tooling applied to a format that is already delivered to the client.

Legality and Personal Use

This distinction between technical feasibility and platform-imposed restrictions matters not only from a usability perspective, but also legally.

Under German copyright law, §53 Urheberrechtsgesetz (UrhG) explicitly permits the creation of copies for private use, including personal backup copies, as long as no effective technical protection measures are circumvented. In other words: making a private copy of lawfully accessible content is generally allowed, provided the access itself is legitimate and no protections are broken.

That legal framework aligns closely with what happens during streaming in the first place. The content is already delivered to the user’s device. Tools like ffmpeg merely allow users to retain what they are already technically receiving—without bypassing DRM, decrypting protected streams, or altering access controls.

The friction, therefore, is not rooted in copyright law itself, but in how access is intentionally constrained at the application and platform level.

Why I Did It

This wasn’t about experimentation or curiosity. It was about usability.

I pay the Rundfunkbeitrag, like everyone else in Germany. The content produced by public broadcasters is funded by the public and exists to be accessible.

And yet, practical access is constrained in ways that feel arbitrary. I can stream the content but not reliably watch it offline. I can view it in a browser but not choose my own player. I can legally access it but not retain it temporarily for personal use or backup in a way that survives tunnels, dropped connections, or travel.

That isn’t fundamentally a copyright problem. It’s a control problem.

I’m not redistributing anything. I’m not breaking protections. I’m not exploiting loopholes. I’m simply taking content I am already allowed to stream and making it usable in the real world.

Closing

I didn’t build this to provoke a debate or make a political statement. I built it because watching Tatort offline—somewhere between Hamburg and Berlin—shouldn’t require workarounds in the first place.

And yet, in 2025, it still does.

Sometimes the only way to solve a simple problem is to write your own damn tools.

Cheers,

Tobi

Comments